On Dyson, techno-centric design and social consumption

7th July 2025See bottom for addendum added on 28/7/25

As a design engineer I’ve spent plenty of time mulling over what ‘good’ design is. The question is complex and is a starting point for reflecting on our role as designers, how design should interact with society and what even constitutes design!

I recently visited the Glasgow Zine Festival and picked up a wee zine about one man’s hatred of James Dyson, which has inspired me to put some of my own thoughts on the topic down in words. I'm going to focus on formal design elements but if you want reminding of James Dyson's billionaire hypocricy I recommend you pick up a copy. Or, just read the news.

Design follows technology

Technology, innovation and advancements can solve problems that make our lives easier and more enjoyable. When working with new technology, designers act as interpreters between the tech and their users – ensuring that users can understand how to use the technology, that it fits their needs, etc.

Dyson tends to adopt an extreme attitude to technology compared to other consumer brands: the technology comes first. That approach worked well for the first wave of innovation for Dyson, giving them a product functionally superior to their competitors. But they then decided to codify that approach into their brand DNA.

The celebration of progress and technology have featured in a number of design movements like Futurism and High-Tech. Showy, impressive and novel, “technology-first” or "tech-push" design may be influential but is cursed to never get the balance right between celebrating technology and user needs. Technology is only useful to the extent that it is, well, useful.

Dyson is no exception and for a long time it seemed to me as if their engineering team held sway over all design decisions. But having thought about it more, I think it’s the opposite; marketing and a certain type of “style follows sales” design are in the driving seat. I’ll explore that more in the next section.

Some examples where I think Dyson products embrace technology to the overall detriment of the design:

- Dyson vacuum cleaners embrace a machine aesthetic, but as a result of their aesthetic angularity they aren’t very comfortable to hold and hard to clean

- The wall-mount for Dyson cordless vacuum cleaners is unnecessarily complex and awkward to use

- Dyson hand dryers are very fast, but as a result, they fling water everywhere and are unpleasantly loud. The drip-tray designs get disgustingly mouldy while stubbornly claiming to be "tested. certified. hygienic"

- Dyson integrated wash and dry taps are awkward to use (violating basic user-interaction design principles), fling water everywhere and block others from using the sink

- Dyson “Contrarotator” washing machines (no longer sold) aimed to wash clothes faster and more efficiently than conventional designs but were unreliable, too large to fit in standard cabinets and damaged clothes

Above: The Dyson V8 Advanced Cordless Vacuum Cleaner, left, and the Bosch Unlimited ProClean Cordless Cleaner, right.

Above: The Dyson V8 Advanced Cordless Vacuum Cleaner, left, and the Bosch Unlimited ProClean Cordless Cleaner, right.

Let’s compare the design decisions made by Dyson and Bosch for their similarly-priced cordless vacuum cleaners above.

The Dyson is styled like a science-fiction plasma blaster with neon colours and metallic-finish plastics, cyclone-heads visible through the top moulding, and an emphasis on geometry in the form. It screams “future”.

In contrast, the Bosch is far smoother, uses darker colours and adopts more ergonomic curves around the handle and trigger. The form is overall less angular, without large protrusions and surfaces are left smooth. The design language is reminiscent of a handheld power-tool (no surprise).

The Dyson certainly embodies the future but the Bosch is the design users will find better to use in the present. It will be easier to clean, show scratches less prominently and be less prone to jabbing the user or objects during use. I am not going to get into comparing tech-specs, but the Bosch is better – go watch a review.

But it’s also unsustainable for any brand to define themselves around constant radical innovation. Dyson can’t create step-changes in technology fast enough to keep other companies far enough behind and patents don’t last forever; indeed James Dyson’s original patents expired in the early 2000s (and it’s a great thing for consumers that they did).

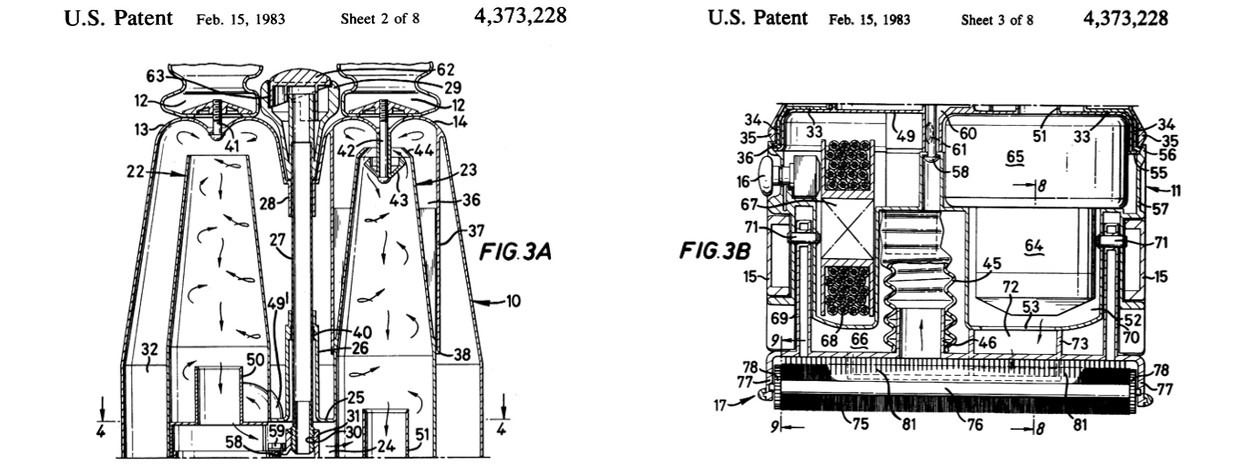

Above: James Dyson patent no. US4373228A, figs 3A and 3B. Available from google

Above: James Dyson patent no. US4373228A, figs 3A and 3B. Available from google

There’s now a plethora of affordable, practical products from companies like LG, Samsung, Shark, Bosch, Miele, Vax and many others. Do you really want to pay significantly more for the marginally superior vacuum cleaner?

Design and social consumption

I don’t, but maybe you do. Or at least, maybe Dyson can convince you that you do.

A characteristic of modern product design is to clearly define brand values and then express these through product design (via form, interaction, materials, etc) such that the user is conscious of what those values say about the product (“it’s the best vacuum cleaner ever built”) and thus of them (“I am the type of person who should own the best-ever vacuum cleaner cleaner”).

As Patric W. Jordan writes in “Designing Pleasurable Products”:

“Material status is conferred by products that give an impression – rightly or wrongly – that the owner has significant material wealth. Objects that confer cultural status are those that give the impression – again rightly or wrongly – that someone is a person of great cultural knowledge and taste.”

“Many products can have a role as “social accessories” – helping to generate or maintain a particular image. People may want to own or use products whose design tallies with their image of themselves”.

Patrick W. Jordan paraphrasing Bourdieu (1979) in Designing Pleasurable Products (2000), page 35

Dyson products are self-image machines as well as vacuum cleaners. This is why the idea that Dysons are the best is so crucial to the company, why Dyson engages in such aggressive legal attacks on the marketing claims of its competitors and why their technological supremacy and extensive R&D activities feature so prominently in their marketing.

But Dyson have managed to extend this socio-consumption to organisations. Because the public had been primed for decades to understand that the Dyson brand signifies modernity and intelligence, Dyson was able to turn public washrooms everywhere into a space for socio-cultural statement-making.

In contrast with their claims of design exceptionalism, I think that Dyson’s focus on social consumption results in compromises in other facets of the design, such as ergonomics, cost and reliability. Let’s take the hand dryers as an example to find out.

Above: Dyson Airblade V, left, Warner Howard EL600, right. Click to open full-size.

Above: Dyson Airblade V, left, Warner Howard EL600, right. Click to open full-size.

The Dyson embodies the machine age with the stainless steel, bold angularity and fighter-jet V. The design language communicates futurism, aggression and performance.

The Warner Howard features a smoothly rounded form (powder-coated cast aluminium) that is easy to wipe clean and which you can’t set a drinks can (or drugs) on. The design language is more ovoid and perhaps medical – reassuring and care-giving. It’s unobtrusive.

This time I can’t resist functional comparison too. The Dyson claims a 10-15 second dry time with a power consumption of 1000W. Your trousers may become wet in the process. The Warner Howard claims 16-20 seconds dry time while consuming 600W. Prices? £615 to £145. Do you value that 5 seconds above all else? Does the purchasing organisation? Does the washroom cleaner?

In the previous section I compared Dyson and Bosch cordless vacuum cleaners. Both expressed traits traditionally considered masculine, albeit in different ways: power, ruggedness, performance. Gender is rarely irrelevant in consumer design and I wonder if this reflects the designers appealing to male preferences, either as purchasers but hopefully, increasingly, as equal users.

However much you like to be reminded of your vacuum cleaner's power, the over-emphasis on statement-making is itself a disturbance from using the product. For many product categories symbolic value allows us to express our individual tastes and values - and that’s great. But for the categories Dyson operate in we largely want to ignore the product, complete the task and get on with our lives.

But the brand Dyson have constructed seemingly cannot design unobtrusive products. Dysons must be noticeably different to alternatives - even if Dyson design engineers considered that a white powder-coated cast aluminium enclosure was the best solution, it's familiar to consumers and thus is not an option. I think Dyson designers very much intend for you to be aware of it when you are using a Dyson washroom product in order to recreate the social expectation for Dyson products. Personally, I find that entitlement to my attention invasive and arrogant.

Indeed, most other hand-dryers and taps focus on washing or drying your hands in a cost-effective, user-friendly and reliable way. That is the work of designers and brands committed to their stakeholders and end users. That is where we will find the best design.

The myth and value of star designers

James Dyson is a prominent feature of the Dyson brand, in which he is presented as a “star designer”; a genius who through resolve and ingenuity can create innovations and great product design. This story has been repeated so many times (by Dyson itself, and eager British institutions) that it's fair to say that Sir James Dyson is a part of the British design canon.

But I don’t think this “star designer” story is particularly helpful or even accurate.

Fixating on individual designers obscures the reality of design and manufacture. Modern products are highly complex and while individuals do make important contributions, all significant innovations require the collaboration of a large number of designers, engineers and many other professionals - even the James Dyson story is crafted not by James Dyson himself but by a team of marketing professionals.

Above: James Dyson, the star designer Click to open full-size.

Above: James Dyson, the star designer Click to open full-size.

Take Thomas Edison – a name almost synonymous with invention itself. Edison progressively assembled a massive research and development team and facility – while he was certainly a gifted, inquiring and driven individual, he certainly did not produce his great innovations alone.

Yet the name of an individual designer continues to carry social status. As Cheryl Buckley writes in Designing Modern Britain:

“The imprint of the designer’s name has been an increasingly essential element in the promotion of design…the mythology of individual design genius has become commonplace in our everyday culture, and the signature of certain designers has added value to all types of design. To some extent such mythologizing has been intrinsic to design ever since designers’ names began to be used to promote and sell goods more effectively, at least as far back as Josiah Wedgwood in the eighteen century”.

Cheryl Buckley, Designing Modern Britain (2007), page 210

Dyson uses the star designer myth to establish certain ideas about James Dyson in the public consciousness (thus also strengthening the star designer myth) which helps convince people their vacuum cleaners are well designed - there's a level of circular logic in the approach.

More importantly, by over-emphasising the role of the individual we present aspiring designers and engineers with an incorrect vision of the profession while undervaluing the importance of teams and collaboration. We also inflate the ego of the star designer to dangerous proportions! It is important to me that everyone who contributes to an endeavour with their care, time and effort should be appreciated. Celebrating the star designer among thousands in an organisation can only detract from this aim.

Thinking bigger than Dyson, it seems to me that an emphasis on individual talent and stardom can lead designers (and consumers) towards gimmicky and frivolous products or features – things which profess too loudly that they are intelligently designed, and away from genuine solutions and tackling tricky and big problems. Design shapes our surroundings and influences the way we think, behave and interact with one another and the planet – it’s a responsibility that should be taken seriously by each individual professional and by the organisations we work for. Attaining celebrity is, at best, a distraction.

It seems to be easy for us fallible humans to identify with the idea that work was done by an individual rather than a team. Yet no-matter how seductive the idea of ‘genius’ is, I think it’s important to stop repeating the myth.

Dyson, techno-centric design and social consumption

Dyson puts an emphasis on design and technology in their products and marketing. It’s undeniable that the company has brought transformative new technologies into homes and changed the expectations for whole markets. Yet inseparable from their genuine contributions is an in-your-face centring of technology in Dyson designs – in their aesthetics, functions and user experience.

As I've argued, the task Dyson has set itself, I think, is to convince purchasers that technology is the primary factor they should value in a product, and that Dyson products feature the best technology.

But as time goes on, that position becomes unsustainable and Dyson are forced to differentiate themselves not just through genuine back-of-house innovation but by simply shouting “TECH!” as loud as possible.

While I haven't researched market data, with disposable income tighter for many people today than when Dyson launched in 1991 and with a corresponding, if not universal, erosion of the faith we place in technology to solve society's problems, the market for premium price high-tech utility products seems challenging. New innovations, such as a screen showing data on the particle size you are collecting, show Dyson remains committed to bringing novel technology into your home – I’m just not sure that new peripheral features can continue to support the same price premium for Dyson.

Dyson products have thus played a part in the 2000s trends of the “deification” and social consumption of technology. This worldview proposes that technology should aim to resolve our every inconvenience and should be available as much in our homes as in industry. Perhaps, suggests the worldview, this is the very point of human endeavour.

I don't think it is, and I think it's precisely what techno-centric design doesn't value about your life that curses Dyson products to forever cry ‘new’ but never to realise the best overall design for a given product. That’s the task for more humble design.

TR

Addendum added on 28/7/25:

After writing this article I posted it to hacker news and discussed the topic with colleagues. This led me to three conclusions:

- People mostly just like to talk about their vacuum cleaner, whatever the relevance to the broader topic. People tend to adopt either (a) strong loyalty to their product/brand, (b) strong dislike of their product/brand, or (c) pointed indifference

- People have strong preferences for different types of hand dryers and will cite a huge variety of reasons, drying time being the tip of the iceberg

- In most cases, people’s reasons for preferring/disliking particular hand dryers are not drying time, but are what I will call “emotional”

All this encourages me that my central point in this post has merit, namely that technology-centric design encourages an over-emphasis on achieving particular performance metrics to the detriment of other factors, such as user-experience.

In fact, this underlines an odd-sounding point that our users are human, and the human user does not make user-centred design easy! Some of my colleagues dislike hot hand dryers because they have connotations of uncleanliness while others prefer them, especially on a cold day. Many expressed dislike for loud hand dryers yet while some preferred the high-rpm whine of a Dyson airblade and others found it intolerable. Some worry about airborne particles, yet some of my most hygiene-conscious colleagues actually liked using “trough” hand dryers where you insert your hands and try not to touch the grimy internal surfaces, citing that the LEDs make them seem modern.

Faced with such a variety of priorities and preferences a pragmatic way forward is surely to offer washroom users a choice of hand dryers, and let them decide.

But, how do we design user-centred products when the users disagree so widely on what good looks like? Designers can (and do) conduct carefully-structured user research and look at trends in preferences, also noting those factors which lead to significant dislike for some users. The outcome, again, is certainly a range of different products, or products which can adapt better to different preferences.