Early modern grain elevators: “listen to the counsels of the American engineers”

1st June 2025Architects in the early modern movement sought an ideological and design revolution, applying modern materials and construction techniques to create ambitious, functional and visually striking designs. They had, however, few architectural precedents to illustrate their theories in practice. An unlikely structure which had just undergone a Modern transformation – the grain elevator – provided a perfect case study. The study of this moment in design history provides a satisfying meander through the same factors which propelled the modern movement in general; urbanisation, globalisation, new materials and new techniques. The question I hope to answer is perhaps the obvious: why the grain elevator, of all structures?

Growing grain

At the turn of the century a new form started to appear in the American Midwest – modern grain elevators, huge structures with the simple task of receiving, storing and dispensing grain in bulk.

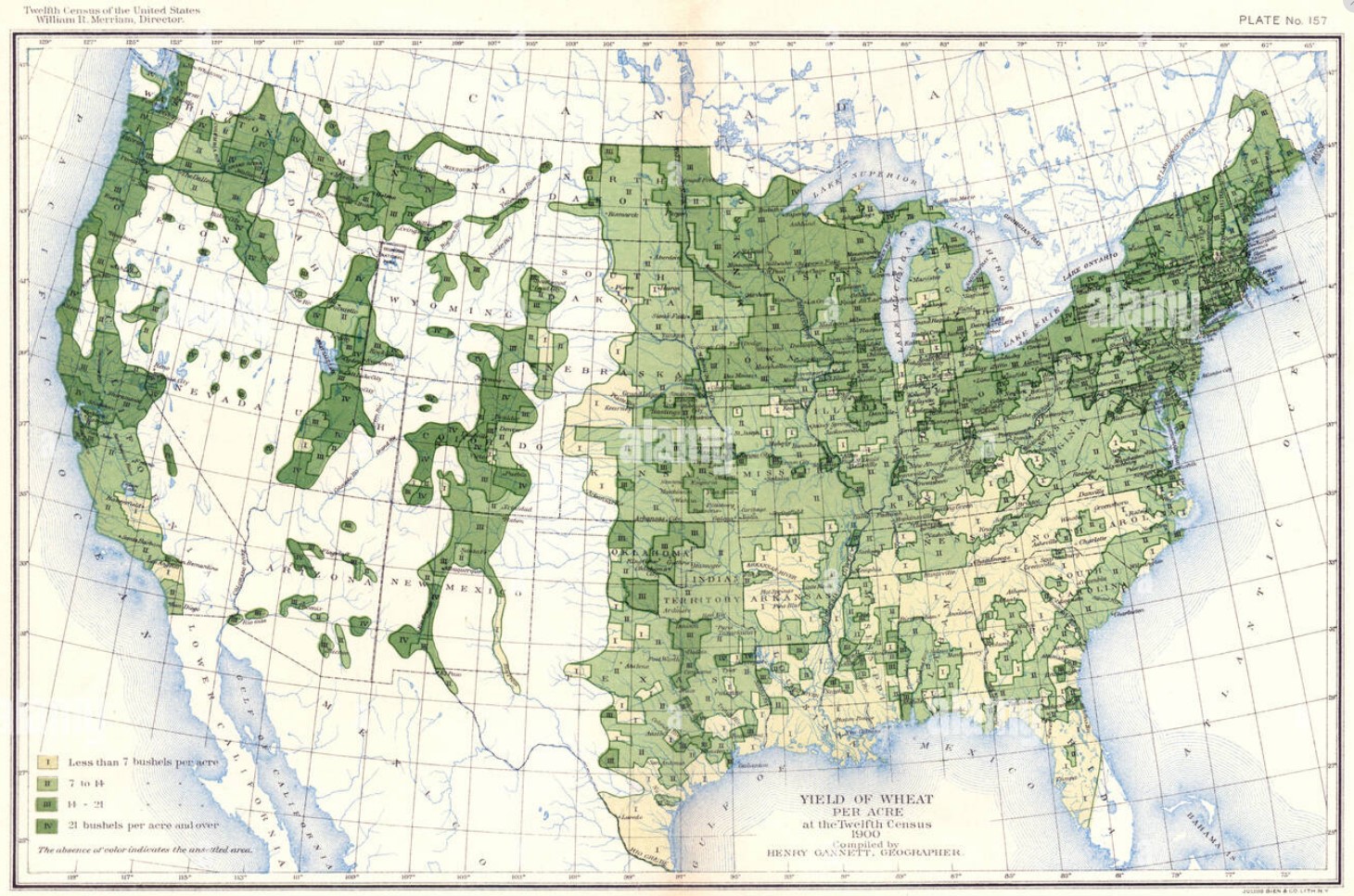

Agricultural production and consumption in the USA and across the world in the 19th century was primarily on a local or regional basis, with limited international trade. By the turn of the century population growth and urbanisation had increased the need for regional trade in grain, to feed cities. At this time grains fulfilled a greater portion of the average person’s diet than today, but grains were also feeds for livestock and horses. Before electric trams or internal widespread use of internal combustion engines in cars/buses, horses powered much of the transport in cities. I made a back-of-the-napkin estimate that horses could have consumed around 25% of grain production in 1900.

The trends of population growth and urbanisation therefore resulted in unprecedented consumption and hence production of grains, leading to a need for new transport and storage solutions. This was felt particularly sharply in the American (and Canadian) cornbelt states producing grain for major population areas like New York and the East coast ports for export.

Above: Grain production in the USA, 1900. Source: Alamy Click to open full-size.

Above: Grain production in the USA, 1900. Source: Alamy Click to open full-size.

Farmers would take their grain to the nearest elevator (which were dispersed at regular intervals along railroads) and unload their grain to be weighed, graded and purchased. The stored grain would lifted in the elevator and deposited into passing steam train wagons in bulk (i.e., not unitised in bags).

These early elevators were wooden and could be produced using local materials and existing carpentry and barn-raising skillsets, but grew increasingly specialised with time. The weighing, elevation, sorting and storage requirements all provided needs which engineers solved with complex mechanisms.

Above: A wooden grain elevator in Manitoba, Canada, with metal cladding. Source: The Guardian Click to open full-size.

Above: A wooden grain elevator in Manitoba, Canada, with metal cladding. Source: The Guardian Click to open full-size.

A major issue with the design was susceptibility to fire. These wooden grain elevators were, by necessity, located along railroads and required steam trains to pull alongside and stop during loading. This posed a severe risk of heat and sparks igniting the elevators, both wooden and containing highly flammable grain and dusts. It was therefore common to protect the structure with a corrugated metal cladding.

While this solution may have been somewhat adequate for the local elevators, at the major logistical hubs, a great number of trains would pass through and the environment was to a much greater extent industrialised. Inside the elevator, extensive and complex systems of conveyors, rollers, hoppers and chutes were all powered by steam engines (or, as time went on, electricity) and the combination of an explosive atmosphere and many sources of friction and heat required a more comprehensive protection from combustion. Thus, in the major hubs, grain elevators needed to be far larger and made from non-combustible materials.

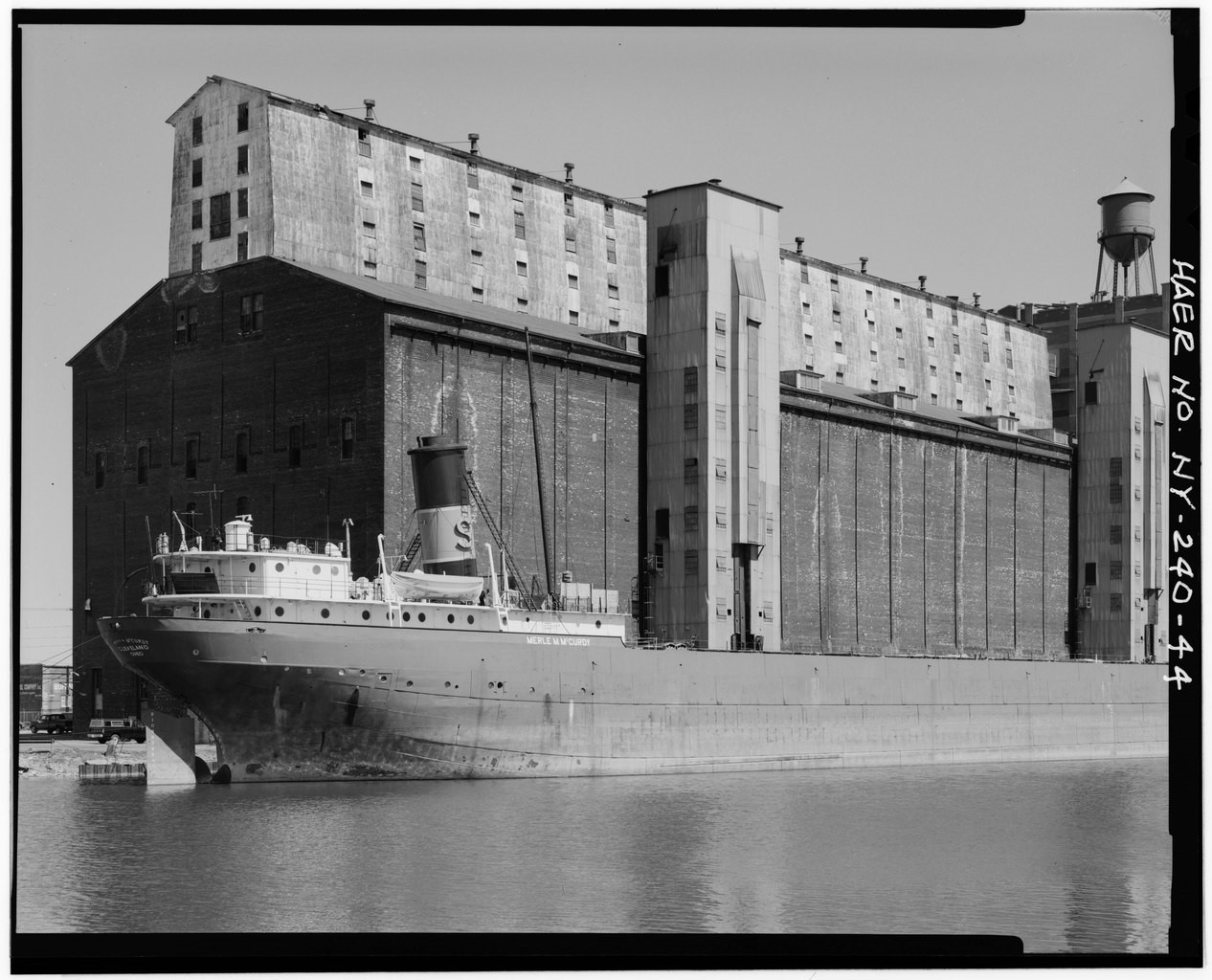

One such hub for grain storage and transportation was Buffalo, NY, and it was here that the largest Grain Elevators were built. Buffalo was in close proximity to a number of major cities in both the USA and Canada and crucially had access to the Eerie canal to enable lower cost transport to the East Coast ports, as well as canal and rail links to the Midwest. Buffalo also had a supply of Hydro-electricity from Niagara falls; in 1895 a 37MW capacity Hydro plant was completed, with generators designed by Nicola Tesla. This may have helped Buffalo grain elevators adopt electricity ahead of their time; the colossal “Great Northern” elevator, a steel frame structure with brick curtain wall, was complete in 1897 and used electricity from the start.

Above: The "Great Northern" grain elevator in Buffalo, NY. Steel frame structure with brick curtain wall. Source: Wikipedia Click to open full-size.

Above: The "Great Northern" grain elevator in Buffalo, NY. Steel frame structure with brick curtain wall. Source: Wikipedia Click to open full-size.

But the "brick box" design was not the solution that would come to dominate for the next century.

Searching for a better solution

1899, Minneapolis. Frank H. Peavy the “elevator king” owns elevators across Iowa and Minnesota and is seeking a solution, probably motivated by insurance costs as this quote from the Northwestern Miller periodical indicates in 1902:

a fire-proof plant of 1,500,000 bushels capacity would cost $195,000, against $150,000 for the wooden, but would save $13,875 per year on insurance. This is a very good saving, and would pay the difference in the cost of construction in less than four years.

Northwestern Miller Periodical, 1902

Peavy appoints Charles F. Haglin, a civil engineer and contractor, who travels to Europe for inspiration but returns with the news that no more advanced solution exists there. Before we return to Minneapolis, allow me this tangent to explore what Haglin would have encountered had he visited Glasgow at the time.

Grain storage in Europe

Speaking to a well-informed Synaptec colleague, I learned that until relatively recently there was a dense industry of grain stores and mills centred around the Clyde, west of the Glasgow city centre. Typically, John R Hume photographed a number such sites in the 1960s, including ones demolished to make space for the Kingston bridge over the Clyde.

I found records of 10 such buildings and can easily conclude that Haglin, visiting in 1889, would have found no examples of ‘modern’ engineering. For reference: Cheapside Street (grain store and mills), Bunhouse road (grain mills), Center street (grain mills), Queen street (grain store), Landressy street, William street (grain store), tradeston street (grain mill), Centre street grain store, Vintner street, Surrey street, Washington (grain mills), West street (grain mills).

Above: Grain store built on Cheapside Street (Anderston, Glasgow) in 1892-3. Source: Mackintosh Architecture Click to open full-size.

Above: Grain store built on Cheapside Street (Anderston, Glasgow) in 1892-3. Source: Mackintosh Architecture Click to open full-size.

The grain stores and buildings were typical of much Glaswegian building at the time, being designed in Sandstone or brick and probably with elements of steel for internal structure. They may have used cast iron internal details to mitigate risk of fire, as can be seen in window-sills at the textile mill in New Lanark. The store pictured above at Cheapside street is fairly representative of the typology (being closer to a warehouse than an American or Canadian elevator) but larger structures may have existed at logistical hubs. There is also an interesting connection to Charles Rennie Mackintosh, as it's noted that he had annotated the original drawings submitted in 1892.

This can be contrasted with later Scottish grain stores at Redding (nearby to Grangemouth, so perhaps providing storage for import/export?) and Shearer street which are clearly reinforced concrete structures, both sited in proximity to rivers and railways.

A concrete solution

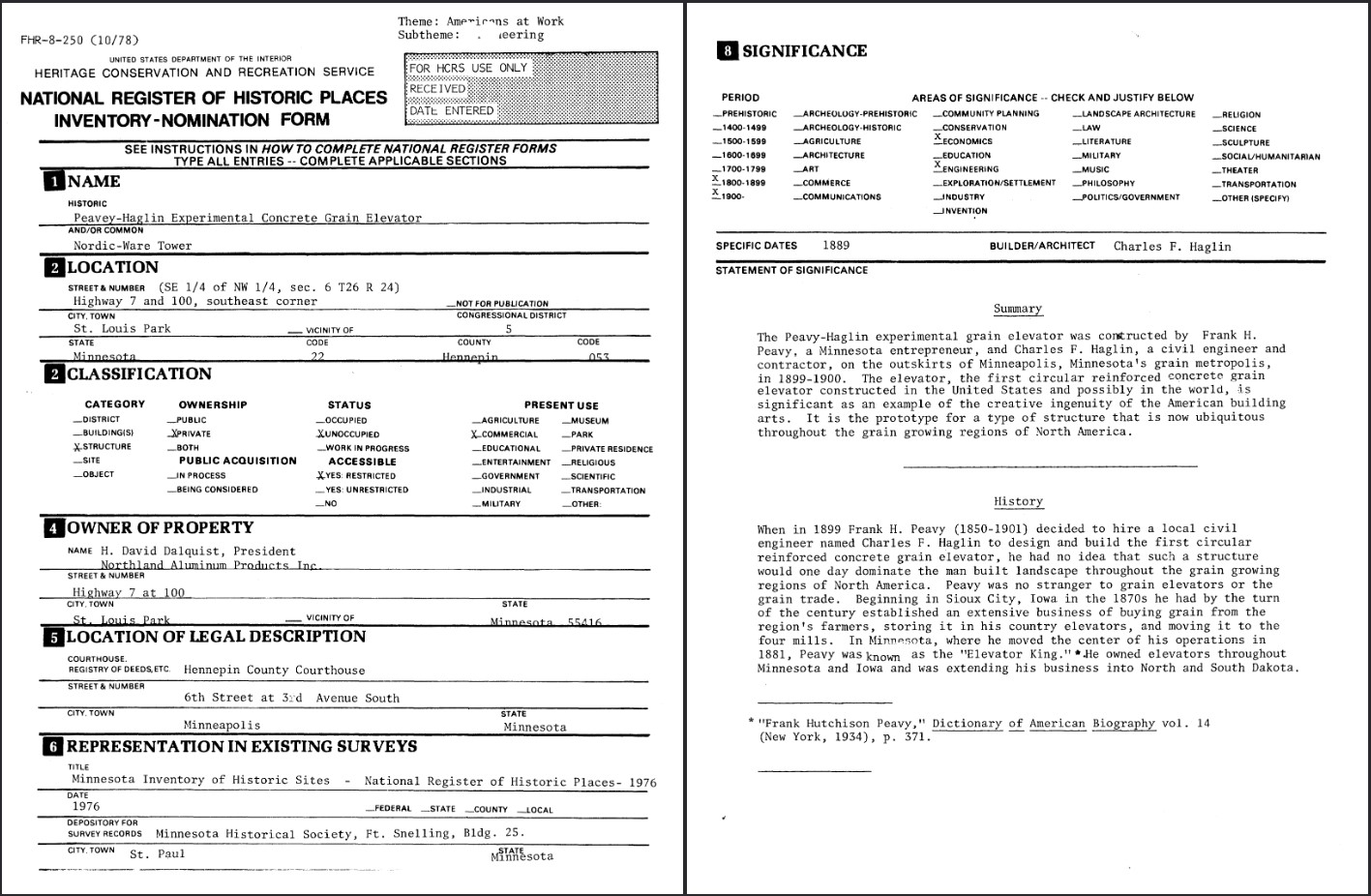

Haglin thus returned to Minneapolis having found no innovative grain storage solution. A 1976 United States National Register of Historic Places form records the solution Haglin arrived at:

Above: Heritage record for the Peavy-Haglin grain elevator. Source: St Louis Park Historical Society Click to open full-size.

Above: Heritage record for the Peavy-Haglin grain elevator. Source: St Louis Park Historical Society Click to open full-size.

“The Peavy-Haglin Experimental Grain Elevator is a single, reinforced concrete cylinder (believed to be reinforced with brass rods)...The elevator, the first circular reinforced concrete grain elevator constructed in the United States and possibly in the world, is significant as an example of the creative ingenuity of the American building arts. It is the prototype for a type of structure that is now ubiquitous throughout the grain growing regions of North America.”

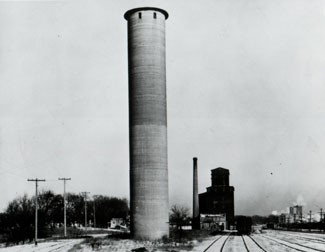

Above: The Peavy-Haglin grain elevator. Source: National Park Service Click to open full-size.

Above: The Peavy-Haglin grain elevator. Source: National Park Service Click to open full-size.

The Peavy-Haglin elevator and those adopting the same solution established the basis for reinforced concrete storage of bulk grain. The principle of this solution would be refined and expanded to produce striking forms.

Above: Grain storage at Hutchison, Kansas - more than 1/2 a mile long. Built 1957. Reference: Centre for land use interpretation Click to open full-size.

Above: Grain storage at Hutchison, Kansas - more than 1/2 a mile long. Built 1957. Reference: Centre for land use interpretation Click to open full-size.

Above: A modern grain elevator in Kansas. Click to open full-size.

Above: A modern grain elevator in Kansas. Click to open full-size.

Inspiration in Europe

Why were European architects so inspired by these structures, as well as other utilitarian examples of American architecture?

Perhaps the most dedicated grain elevator appreciator was Le Corbusier who included 9 images of American and Canadian grain elevators right at the start of his 1924 book Vers Une Architecture, which reached the UK in 1927 as Towards a New Architecture.

Before quoting him, I’d like to point out that while the influence Le Corbusier’s writing had is undeniable it should be reflected on critically, bearing in mind both the limits of his writing (his arguments are often more supported by prose than a consistent chain of logic) and his Fascist apologism. While discussing problematic individuals and their ideas naturally brings prominence to them, it also offers a chance for critical reassessment.

So, why were grain elevators such an important reference for Le Corbusier and peers? I’d say there are two reasons; they (1) satisfy his aesthetic theories and; (2) illustrate his argument that architectural solutions must be arrived at by logic (rather than repeating existing solutions).

For aesthetics, Le Corbusier’s favoured the use of bold, large in scale and clearly comprehensible geometric forms in architecture. He saw these as expressing honesty and morality, as well as exciting and satisfying the human eye because the whole form could be clearly comprehended.

“if [the] masses are of a formal kind and have not been spoilt by unseemly variations, if the disposition of their grouping expresses a clean rhythm and not an incoherent agglomeration, if the relationship of mass to space is in just proportion, the eye transmits to the brain co-ordinated sensations and the mind derives from these satisfactions of a high order: this is architecture.”

Le Corbusier, "Towards a New Architecture", 1924

Indeed, many major grain elevators adopted a design based on consecutive cylindrical silos, creating a massive, sublime and rhythmic form. Being located in typically flat areas further emphasised their scale and perhaps provided a symbol of engineering prowess. The austerity of their form would have appealed to Le Corbusier; he aggressively rejects ornamentation, decoration and the repetition of existing architectural styles. (Content warning: racism and classism).

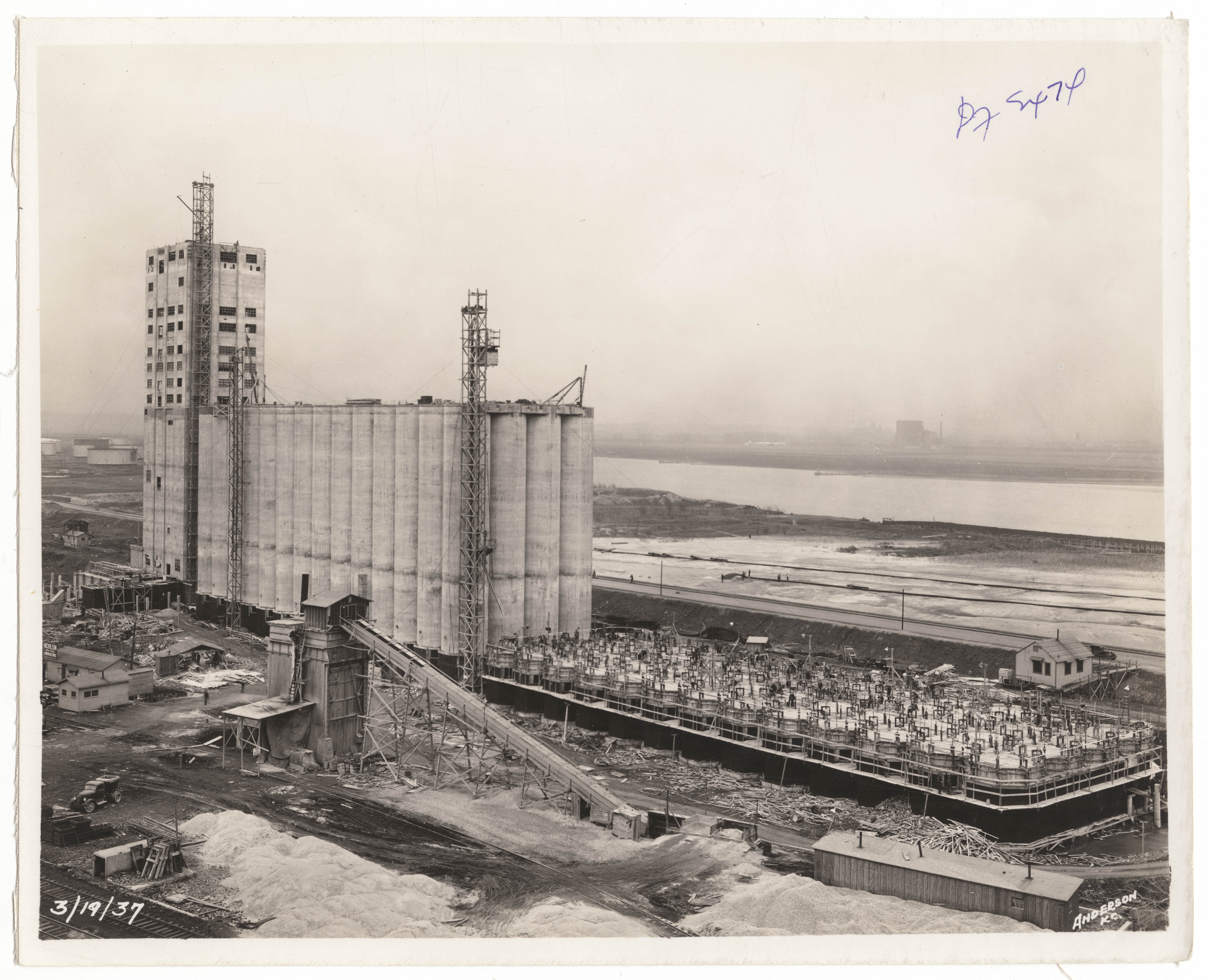

Above: Construction of a grain elevator in Kansas City. Constructed after Le Corbusier's Towards a new architecture it's nevertheless easy to see how the design embodies his theories. Source: Kansas City Public Library Click to open full-size.

Above: Construction of a grain elevator in Kansas City. Constructed after Le Corbusier's Towards a new architecture it's nevertheless easy to see how the design embodies his theories. Source: Kansas City Public Library Click to open full-size.

“Decoration is of a sensorial and elementary order, as is colour, and is suited to simple races, peasants and savages. Harmony and proportion incite the intellectual faculties and arrest the man of culture.”

Le Corbusier, "Towards a New Architecture", 1924

He also argues that Architects who specify decoration “[make] other people-masons, carpenters and joiners-perform miracles of perseverance, care and skill”. These quotes strongly reminded me of both the arguments and wording of Adolf Loos (who openly states his white supremacism, along with a hatred of seemingly everything, in Ornament and Crime). Le Corbusier was greatly inspired by Loos, writing "Loos swept right beneath our feet, and it was a Homeric cleansing" (The Private Adolf Loos). This influence is clear to see, with Loos writing in 1898:

“Ideally, the building speculator would have the façade stuccoed smooth from top to bottom. It’s the least expensive way of doing things. And if he did so he would also be acting in the truest, the most correct, the most artistic way.”

Adolf Loos, "Potemkin City", 1898

And in Ornament and Crime (1908):

“ornament does not enhance my joy in life, nor does it that of any cultured person”

Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime, 1908

Then in 1910:

“The tiniest details are drawn in on a scale of 1:100 and the bricklayer and stonemason have to chip out or build up the graphic nonsense by the sweat of their brow.”

Adolf Loos, Writing for Neue Freie Presse, 1910 (ref)

In terms of architectural design, Le Corbusier felt that in the machine age architects should adopt more of an engineering attitude where material selection and design are outcomes of a rational and logical decision-making process in response to a well stated problem. He states that:

“We are living in a period of reconstruction and of adaptation to new social and economic conditions. [We] will only recover the grand line of tradition by a complete revision of the methods in vogue and by the fixing of a new basis in construction established in logic.”

Concrete and steel grain elevators were thus clear examples of a new technical requirement being born of evolving economic and social conditions. American engineers had applied logical problem solving to the problem and reached a novel architectural solution, uninfluenced by historic typologies. Thus the reader is encouraged to “listen to the counsels of the American engineers. But let us beware of American architects!”.

My reflection

This topic caught my interest for a couple reasons. I had no real knowledge about grain elevators and learning about their evolution and the gargantuan forms they would take was amazing. I also like exploring the connections, experiments, trends and thought-processes that gradually built up the Modern movement, but remembering that they all existed in a socio-economic context. At first I found it amusing that Le Corbusier was so fascinated by the American/Canadian grain elevators, citing them alongside the likes of the Parthenon - but if I can feel shock at the scale of an 1898 building through an image then it's easy to imagine how European Architects of the time would have too.

While I know that Adolf Loos had visited America, I don't know how many of the European Architects who lauded American structures would have, especially given the outbreak of the First World War. This must have added an element of exoticism, that seductive argument that the correct path has already been shown elsewhere and that we are falling behind!. I thus think the grain elevators served polemicists like Le Corbusier best with their drama and symbolisism, and would explain why he does not explain or explore their design or relevance at all in Towards a New Architecture. With their huge scale, stark design and novelty they communicate ambition, urgency and change to the reader.

But, poignant as that symbol is, as with many of the grand buildings Le Corbusier enthuses over in Towards a New Architecture, there's an aesthetic thinness to it for architects mainly designing more complex programs. Homes, universities, schools, hospitals, theatres, churches, halls, even factories - these buildings have many more functions to fulfil than just holding grain. Le Corbusier uses grain elevators to support his aesthetic theories, but therein lies the problem in translating the same aesthetic theory onto radically different buildings. It's easy to admire the scale, artificial form and utilitarianism of industrial buildings; I'm not sure a universal design theory can be supported by that emotion alone.

TR

I’ve been reading:

Towards a new architecture, Le Corbusier (1927)

Ornament and Crime (and selected works), Adolf Loos (1897-1924)

"What Modernism Learned from the World's First Grain Elevator" www.frieze.com (2019)

"Evolution of the Modern Elevator", www.buffaloah.com (2002)

"Silo Dreams: The Industrial Inspirations of the Modern Movement", www.moma.org (2023)